America’s “Anti-Slavery Father” Was Also a Great Dad

“He is my anti-slavery father,” remarked William Lloyd Garrison in 1853, in reference to Rev. John Rankin of Ripley, Ohio. “His book on slavery was the cause of my entering the anti-slavery conflict.” Countless other early abolitionists shared Garrison’s sentiment.

Despite being all but forgotten in our current day and age, John Rankin was considered the “father of abolitionism” in the mid-nineteenth century. He provided the anti-slavery movement with an intellectual and spiritual foundation on which to build.

But to his 14 children, John Rankin was more than the mind that sparked the anti-slavery movement; he was a great dad.

Integrity > Convenience

By the time Rankin’s first child was born, he had already committed himself to the anti-slavery cause. His ministry began in eastern Tennessee, where he was born and raised. One Sunday in 1817, Rankin gave a sermon in which he preached that “the teaching of Christ was opposed to all forms of oppression” and thus it was the duty of all Christians “to drive oppression from the earth.”

While there was no direct reference to slavery, the church elders could read between the lines. Rankin was presented with a choice; he could continue to preach against slavery, or he could continue to preach in Tennessee, but he could not do both. With that, Rankin resolved to move his wife, Jean Rankin, and his son, Adam Lowry Rankin, to live in the free state of Ohio. Presented with the opportunity to take the route of least resistance, Rankin demonstrated to his son that integrity was more valuable than convenience.

It would be several years before young Lowry could fully comprehend this lesson (he wasn’t even a year old when the Rankin family started their journey to Ohio). But throughout his life, Lowry and the rest of his 13 siblings faced several opportunities to imitate their father’s example.

A Little Red House

John Rankin finally settled in Ripley, Ohio, after crossing the Ohio River with his family in 1822. It didn’t take long before he was integrated into the pre-existing community of Underground Railroad conductors. The red brick home he built for his growing family sat on the hill behind the village. For the fugitive slave who could see a lantern lit in the window at night, Rankin’s house was a beacon of liberty. It wasn’t long before hundreds were coming through his hilltop home in their escape from slavery. This operation was only made possible by the assistance he received from his sons.

In the early years, Rankin would have to see to it himself that any fugitive stopping at his station would make it safely to their next stop. This would often be an exhausting, all-night ordeal as he would escort them to the next station. As his sons reached an appropriate age, they would help distribute this workload, often going in his place. This wasn’t a responsibility that Rankin forced upon his sons. Each of them joined their father’s Underground Railroad efforts entirely of their own will.

It may seem remarkable that so many of Rankin’s children were willing to risk their own safety in the service of people they had never met — as teenagers, nonetheless! This was a direct result of the values that they were imbued with by their parents.

Certainly, the integrity of their father served as a great example to follow, but they had also been raised with an overwhelming sense of duty. Rankin taught his children that God had a specific calling for each of them, and it was their responsibility to answer that call. When presented with the opportunity, they didn’t hesitate to step up.

Grace Despite

But what may have had the greatest impact on Rankin’s children was his frequent ability to exercise grace. Growing up, the Rankin children watched their father embrace all walks of life. Background, skin color, or prior mistakes didn’t matter to him. When a local drunk appeared at his door ashamed, for instance, Rankin brought him inside, clothed him, and nursed him to health.

On a more personal occasion, when his brother, Thomas, surprised him with the news that he had purchased slaves, Rankin didn’t lash out in anger. Rather, he encouraged Thomas to divorce himself from slavery through a series of public letters — a method that eventually produced its desired effect.

As these letters spread, they served the public as the intellectual foundation for the anti-slavery movement. But to his family, they demonstrated his commitment to grace in the face of what felt like the ultimate betrayal.

Throughout his life, Rankin understood how people looked to him for guidance. Several abolitionists at the time gave in to division or vengeance in their fight against slavery. John Rankin rose above it. He was both courageous and gentle. He could be determined and graceful. The abolitionists looked to him as a leader, but his children looked to him as a loving father. Today, Rankin’s example of conviction, integrity, and grace should be imitated by all fathers.

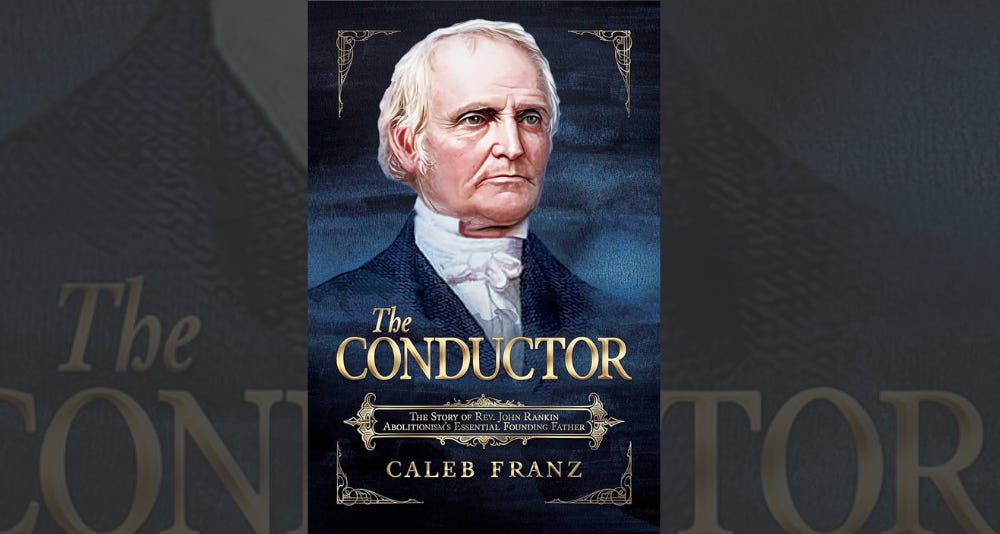

Caleb Franz is the Program Manager with Young Voices and the author of The Conductor: The Story of Rev. John Rankin, Abolitionism's Essential Founding Father, to be released October 15, 2024. It’s currently available for pre-order.

I like to think I've been around but I would have had a hard time saying why slavery was morally wrong. Forgive me for saying that, but I'm going to remember “the teaching of Christ was opposed to all forms of oppression.” Unfortunately, I'll still struggle in defining oppression.